“I’m going to kill God and I’m feeling pretty nervous about it,” I told my mom one evening after school. “I can’t believe I’m gonna be the one to do it, out of everybody in the entire grade, they chose me!”

“It’s a big responsibility, Ryan,” my mom answered, chuckling. “Though you shouldn’t say it like that. That’s pretty sacrilegious, buddy.”

I wasn’t entirely sure what “sacrilegious” meant when she told me that, but I sensed it meant something bad, so I decided to obey. Maybe I’d say something like “Next month, I am gonna make God die” or “The person who crucifies Jesus will be me” when I want to tell people the news.

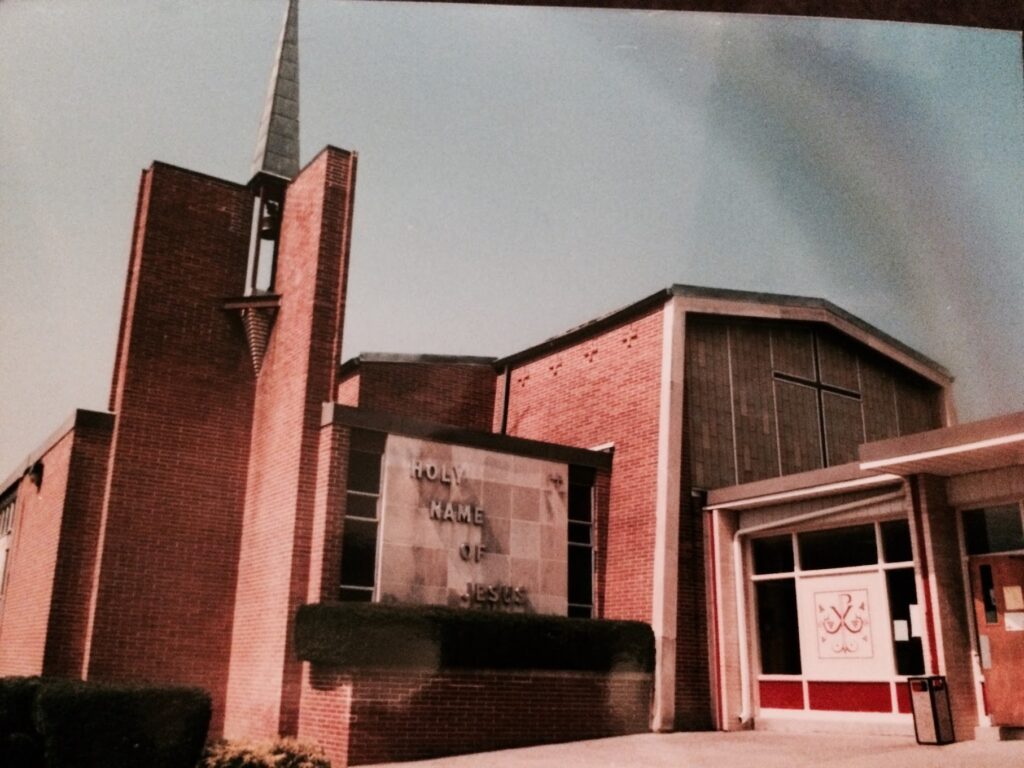

Ms. Mahoney, the art teacher and play coordinator, selected me to play the role of Pontius Pilate in The Stations of The Cross. A dramatic interpretation of the death of Jesus Christ, fully realized by a group of eighth graders, performed at the same altar we had our weekly Mass. Pilate, the lead, was by far the biggest honor that could be bestowed upon someone at Holy Name of Jesus Catholic School (for Kindergarten through Eighth Grade) in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Every single year, the entire diocese would gather and witness a pimply boy condemn another pimply boy dressed as Jesus to his bloody demise on a gargantuan splintering cross. It was a tradition beloved by all, whether it was the faculty who saw their students attempt empathy with the story of Christ or students who simply got out of a math class. I thought it was just like regular church except cool, like a movie adaptation.

Mahoney oversaw the entire production every year. She was an ancient relic of Holy Name, a towering woman in appearance and personality with decaying blonde hair wrapped a bun and pipsqueak glasses. Her uncle, Father Mahoney, was the head priest of the church for decades before his retirement. She was relatively recluse from the rest of the school, residing in the “Art Trailer” behind the primary building and connected church. The small shack was a hoarder’s paradise, complete with props for the musical, plastic religious artifacts, and elementary school art supplies.

Every week, we’d trek outside and proceed single file into her cluttered hut where she sat behind a boundless desk, waiting. She never seemed to move from behind that desk, and would shrilly yell to the furthest reaches of the classroom. Sometimes during a hand turkey or Christmas ornament crafting session, she’d play kickass Christian rock hits from her MP3 player.

It seemed she hated children as she’d infamously flip when faced with any trace of rambunctiousness or error. A “Mahoney moment” we called it. Oh, Brendan spilled the glue again? That’s judgement. Meredith disobeyed the assigned seating chart? That’s discipline. Ben laughed during noontime prayer? That’s damnation. Luckily, she seemed to take a liking to me because of my outwardly reserved, obedient nature. And once she got a load of my acting chops as The Magic Mirror in our production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, she was poised to let me be the one to kill God.

I rehearsed my lines day in and day out. Sometimes at the dinner table, to the annoyance of my family. Sometimes on the bus, to the annoyance of peers. Sometimes in my bedroom, to the annoyance of my goldfish. “Are you the king of the Jews?” “What crimes have you committed?” “I wash my hands of this crime, his blood will not stain my hands,” I shouted.

If I were to be the most powerful man in Judea, I needed to really get inside the mind of the character. What would I do if I were a governor in the year 30? Probably eat a bunch of grapes off the vine and sit in a big throne and kill people. I decided to not engage in the latter because real blood freaked me out. My younger sister wasn’t too keen on feeding me grapes as I reclined in our living room to help me prepare for the role, even though I told her my method acting was absolutely essential for the good of the parish. I even wore some of my mother’s jewelry so I’d look more regal and gaudy like an ancient Roman.

Participation in the Stations of The Cross was mandatory for all eighth grade students. The jocks were casted as macho Roman guards, the cheerleaders were Christian mourners and everybody else excluded from this binary played heretics or high priests who’d call the human-incarnation of the Lord a blasphemous criminal.

Then there was me and Jesus himself. The chosen one, or, the one chosen to play Jesus, was a boy named Nate. A little messiah with Pee-Wee Herman hair and a bad lisp (which is the reason, I think, Mahoney didn’t give him any lines). He transferred into our school only a year prior. An outsider, kind of like Jesus when he made a splash onto the scene way back in the year zero.

Our extreme rehearsal schedule required us to stay after school on Thursdays and Fridays for about two weeks leading up to the performance. Each time we’d arrive in the church for practice, Ms. Mahoney was already there in the far right corner, silent with a director’s intensity.

“Quit monkeying around and get into your positions!” her voice cracked. This was probably directed toward a boisterous boy named Michael; he was famous for his defiance and monkey impressions, puckering his lips and itching his armpits for a group of boys picking up Roman soldier garments and plastic helmets.

“Stop laughing! Do you know where you are right now? Don’t you dare disrespect this church,” Mahoney hissed. “Now, boys, go into the back into the sacristy and change into your costumes. Girls, go to the bathrooms.”

The sacristy was the area located behind the altar where the sacred things are kept. Kind of like a celebrity green room for clergymen. At once, the boys began to tear off their white and navy uniforms, some slapping their bellies in amusement, others went off to the corners to hide their love handles. I was the latter. The priests’ robes hung in a gothic closet, a color for every Christian occasion! Vials of secret oils sat in a cabinet just out of reach and many other props used for mass laid about. Off by myself, I snooped and found the cupboard where they kept the bottles of wine and communion wafers. There were a bunch of little plastic baggies holding pieces of Christ’s flesh, like a cannibal’s doggie bag of leftovers. They seemed much less important when sitting in the darkness in bulk quantity, instead of the singular treasures we received during the sacrament of Holy Communion. I wondered if these bits of Jesus were manufactured by a machine that bakes, cuts, and packages them for wholesale. Perhaps they came from a Catholic Costco. The bread broken in church didn’t seem much different from a loaf of Sara Lee at the supermarket.

I stood almost naked in front of a statue of the Virgin Mary before I slipped into all black. I draped myself in a kingly purple sash, tightened a gold sequin band around my head, and paced with my hands behind my back. My lines raced out of my mouth, “You have brought this man unto me, as one that perverted the people. Behold, I, having examined him before you, have found no fault in this man touching those things where you accuse him.”

***

“It’s showtime!” Ms. Mahoney yelped at us the day of our performance. We stood huddled on the handicap entrance rampway, blocking the path for people with disabilities to come watch our crucifixion. I peeked out of the hallway to locate where my family was sitting. It appeared everybody I was related to in the greater Harrisburg area was here to witness me kill God, from my greatest grandparent to my smallest cousin (about 4 years old). Only here is a crucifixion deemed “fun for the whole family.” Holy Name saw one of its widest audiences in years as we were the first class to do the Stations of the Cross in the newly built church.

The new Holy Name Church completed construction only a few months prior. A reddish brick behemoth, the building was architecturally different in every way from the rest of the run-down school, like a dollhouse sitting next to the Empire State Building. Its entrance enforced by large white columns like teeth and a front-facing circular window that made the House of God look like a cyclops. The magnum opus to the diocese and a monster to the children.

For the dedication ceremony, the big bad Bishop came and had this to say: “You see this edifice that has been built, this beautiful church of the Holy Name of Jesus. Actually, it is not the Holy Name of Jesus. You and I are the church. This building is magnificent because it houses the body of Christ, you and I are the body of Christ.”

What was the point of going through the trouble of building this whole temple if we are the church? Maybe it was spectacle, maybe it was hubris, maybe it was the massive amounts of dough Holy Name would collect now that it was the biggest Church in all of south-central Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, the teaching staff was halved, our books were worn like old socks, and half of our classes were taught in a glorified Hooverville (see: Art Trailer).

Inside the beast of a sanctuary was magnificent marble and stained glass taken from churches that had been demolished. Crowds formed in the narrow lobby where Christians took phone calls, lulled crying babies, or took a discouraged break from the gospel. Beyond the doors, a sprawl of newly cushioned pews and polished sandstone tiling, air-conditioned to the max. The boundless walls painted yellow reached to the stars, represented by huge dangling chandeliers. Statues of Jesus, Mary and Joseph—the whole gang—towered before an ocean of plainly-dressed worshippers.

We sputtered our way through The Lord’s Prayer for good luck, led by Mahoney, before getting into formation. The pre-show jitters picked at all of my nerve endings as I walked out before the altar and sat in the chair reserved strictly for pastors. Allie, the typical pretty, popular, parents-who-donated-the-most-money girl was the one to lead the show with a prayer and introduction:

“Thank you for being here this evening, and joining us as we, uh, enter more fully into Jesus’ suffering tonight. In the penitential spirit of Lent, the Stations act as an examination of, uh, the conscience, allowing each of us to look into our own hearts and find the ways we have drifted away from God. Please turn off all cell phones and enjoy.”

Angry mobs of middle schoolers surrounded the front of the shrine, in complete silence at first. Allie let down a blue veil that obscured her large brown eyes and spray tanned skin. She served as our class’s coveted “good singer” so she chorused over dramatic slow motion interludes between the action of scenes. A lot guilt-tripping and heart-string pulling. She may as well have sang, “This is all yoouurrr fault!”

Action! The entire cast erupted in loud chatter and moaned about the one called Jesus who’s been weaseling in on their religious and civil territory.

“Let him be crucified!” They growled with surprising intensity.

“Hail, King of the Jews!” That one was sarcastic.

“Where’s your God now in your hour of need?” Ouch. That one must’ve cut deep.

Nate just took the thrashing of a lifetime and quietly stood, tied up by a couple of the beefier teens posing as guards. They liked shoving Nate around anyways, but now it was done for the enjoyment of hundreds.

Allie’s narration introduced me, the ruler of Jesus’s fate. I stepped forward with a stern pout. Before taking my position, anxious tingles shook around in belly. I dreaded the moment the entire play would fall on my shoulders. However, when I let the power of the dead Roman fill me, I felt more confident than I’d ever been, standing where God possessed a priest every week to deliver sermons and sacraments. Maybe it was just that I had a couple of tough bodyguards, but I felt extremely powerful like I could totally kill a God right now. I am Pontius Pilate and I’m about to create your faith.

“Why do you summon me befoRe you?” my voice cracked. Shit (I just learned that word). I hoped nobody noticed, I tried to make my voice sound as deep as possible.

“This man here, Jesus of Nazareth, claims to be King of the Jews,” Michael, the monkey boy told me.

“He is spreading lies and must be punished!” said Brendan, the glue-spiller.

“And what shall I do with this man called Jesus?” I asked, thunderously.

A flurry of vicious “crucify him!”s were flung in my direction. Jeez! I put up a hand to signal to them to chill out.

Poor Nate, they really wanted to see him die. I delivered a cutting monologue about how I see no fault in Jesus but I will sentence him to death because I am a good leader who gives the people what they want. In a rare moment of tender emotion, Ms. Mahoney wept. Granted, she did this every year but I still did it! My servant brought me a bowl of water and “I washed my hands of this crime.” No guilt for this governor. I would like to be saved, please and thank you.

After I told him that he was going to die anyways, the entire church halted in prayer once more as Allie sang. Jesus was then brought into the sacristy and, in an instance of showbiz magic, the soldiers whacked their belts against the walls to make it seem like he was being tortured. As this happened, another student painted him with red and black paint to replicate wounds. He shuffled back out, defeated, and had the infamous crown of thorns placed on his head. We watched as he carried the cross the whole way up the aisle and back down before he was “nailed” to the cross, which in this case, meant he just had to keep his hands raised up without moving and pretend to die. I made sure to look very sad, which was something I was quite good at from years of actually being quite sad.

Nate did exactly what he was destined to do that day. His shirtless, skinny body revealed itself for the churchgoers to marvel at. He was casted for this part because of his frailty and pitying eyes, which really helped sell the whole sympathy thing. I couldn’t imagine myself standing in his place like that. Mostly because the thought of that many people seeing my bare body petrified me. Nate’s head went limp. Allie at the microphone said Jesus’s last words for him, “It is finished.” Nate did a little twitch to signal to everybody that “Yes, I am in fact dead now.”

My role required me to feel terrible about my implication in the man-god’s death. I shook my head, condoning what I just witnessed. Though, on the inside I felt free, like I was no longer beheld to soul-crushing tyranny of Catholic middle school. Joy filled my stomach like warm soup, knowing I was responsible for Jesus’s death sentence. I don’t think I was or am a psychopath. I’ve never wanted anybody to die, not really. I knew this was fake and I knew Jesus would make his triumphant return in a couple days. Resurrecting, just as the scriptures foretold. But I would not be returning. This was the end of Lent, which, in my eighth grade year, meant the end of my time in Catholic school.

The following year, I planned my (not-so-triumphant) return to public school, high school. My family couldn’t afford to send me to the newly built Catholic high school, where almost all of my classmates were going. (Side note: Their mascot is “the Crusader,” named after the religious conquerors of the middle ages who slaughtered nonbelievers in the middle east). This meant no more religion class. No more mandatory mass. No more Holy Name and no more standards. Well, there’d still be standards, just different ones. Ones instilled by the government and not God. And thank God there’s nothing wrong with the government! One of my final acts as a Holy Name student was killing God, and now he was buried out of sight and out of mind.

We finished our performance of the Stations of the Cross and everybody prayed. Bows seemed a little inappropriate but we did them anyways. Nate came out with a cheeky smile, and despite what I’d just done to him, we joined hands and let the applause wash over us. My grandparents got me a bouquet of flowers in celebration, but for me it was a kind of joyous mourning. Ms. Mahoney cornered me after I was out of my costume and told me I was one of her favorite students. Not exactly sure what qualified me, but I took her compliment none-the-less. Afterwards, we all went to a Pizza Hut buffet and let out inner-gluttons out.